Joy as Healthcare: Advancing Health Equity for Gender Expansive People

This story was contributed by AB Winter (they/them), Hannah Newcombe (they/them), and Serin Bond-Yancey (they/any) on behalf of the Transgender Health and Wellness Center of Washington (Trans-Wa). Contributors like AB, Hannah, and Serin—and organizational partners like Trans-Wa—bring new perspectives to Community Commons. We believe that the most innovative, sustainable strategies are shared and inspired by those working on the ground. We see community stories as critical building blocks in advancing equitable well-being—by sharing stories from different voices, we can learn from each other and spread lasting change for the greater good. Click the embedded links to learn more about the CC Contributors Network and our foundational work in Taking Action for Trans Rights.

---

In recent years, there has been more recognition of how joy is a powerful contributor to overall health and well-being. “Joy” has also become an increasingly noticeable buzzword—from phrases like “sparking joy” and “joy marketing” to countless social media hashtags, joy is a welcome antidote to COVID-era isolation, disconnection, and stress.

Unfortunately in the U.S., not everyone has equal access to things and circumstances that are most likely to bring about joy—joy is often more readily available to more privileged population groups. This inequity, and the relationship between joy and liberation, are two of the main reasons we see marginalized communities rallying behind messages of celebration, joy, and pride for their identities. It is also a primary reason we see backlash to these efforts; oppressive systems do not want to be interrupted. Black joy, Trans joy, Queer joy, and other forms of joy rooted in liberatory movements are critical for marginalized communities’ self-empowerment, collective care, and well-being.

In public health and related fields, changemakers can support marginalized communities in cultivating joy by advancing joy equity—a state in which every person has a fair and just opportunity to attain their highest level of joy. Below, we share how The Transgender Health and Wellness Center of Washington (Trans-Wa) is cultivating joy and advancing joy equity in their communities, as well as the evidence base behind joy as healthcare, the relationship between joy and LGBTQ+ mental health, and starting points for changemakers to take action.

Joy, Happiness, and Health

Healthy People 2030 highlights the centrality of one’s feelings and emotions in health status, defining health and well-being as “how people think, feel, and function—at a personal and social level—and how they evaluate their lives as a whole.” Emerging bodies of research are delving deeper into the relationship between health and positive emotions like joy. Building on concepts like positive psychology, social connection, social capital, asset mapping, strengths-based solutions, and the thriving framework, this new research continues a trend toward recognizing the profound impact of positive emotions on overall well-being.

On an individual level, experiencing joy and happiness has been shown to reduce stress and improve mental health symptoms and conditions. Joy also has significant impacts on physical health—research links joy and happiness to reduced risk of stroke, and improved brain health, heart health, chronic pain mitigation, immune system function, and even life expectancy. At the community and population level, fostering joy and happiness can lead to healthier communities. When individuals experience positive emotions, they are more likely to engage in health-promoting behaviors, seek preventive care, and support collective well-being.

Joy Equity Is Health Equity

Because joy is important for achieving positive health outcomes, health equity efforts should include the equitable distribution of and access to opportunities to cultivate joy. This is particularly important for communities who are disproportionately impacted by systems trauma, intergenerational trauma, violence, exclusion, isolation, and other factors that make joy more challenging to cultivate.

LGBTQ+ People and Mental Health

LGBTQ+ individuals face unique health challenges that impact their mental health. The relationship between LGBTQ+ health and mental health outcomes is closely tied to societal attitudes, discrimination, and internal and external conflicts related to their identities. Research consistently shows that LGBTQ+ people are at a higher risk for mental health disorders, primarily due to minority stress—chronic stress faced by members of stigmatized, minoritized groups. This stress is often compounded by direct experiences of discrimination, rejection, and the internalization of negative societal messages about their identities. Moreover, healthcare systems often fail to provide inclusive and affirming care, exacerbating health disparities and contributing to adverse mental health outcomes.

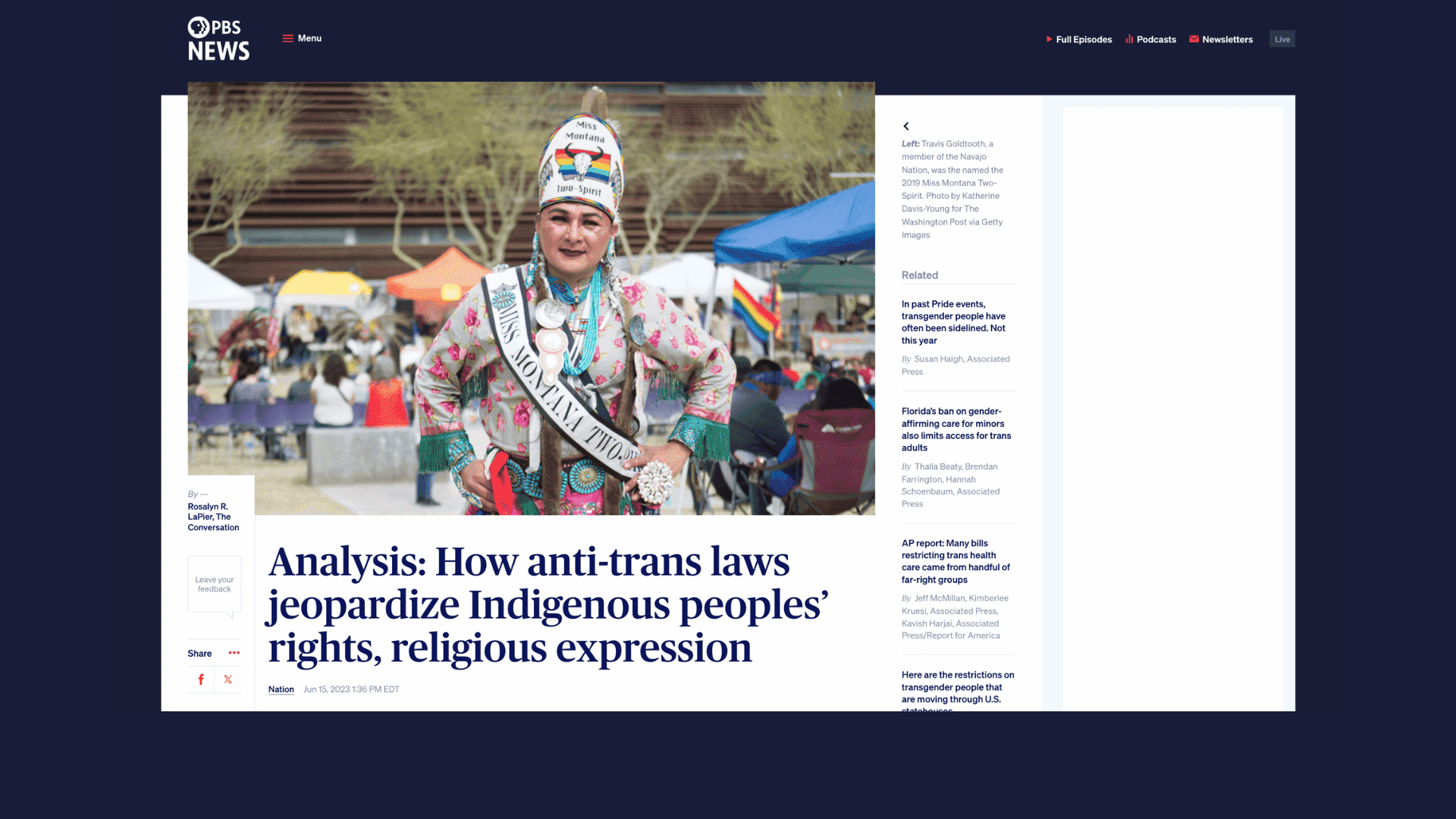

Within the LGBTQ+ community, gender-expansive people—people whose gender assigned at birth doesn’t fit their lived reality—are generally the most impacted by health inequity and most likely to experience negative health and mental health outcomes. This includes people who are transgender, intersex, Two-Spirit, agender, and other nonbinary genders.

Several specific conditions disproportionately impact the mental health of LGBTQ+ individuals. Gender dysphoria—psychological distress that results when a person’s gender does not align with their sex assigned at birth— is prevalent within gender-expansive communities. If not appropriately addressed with professional support (such as therapy and/or medical interventions) gender dysphoria can lead to severe anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. Social isolation is another critical factor; many LGBTQ+ individuals experience isolation due to estrangement from unsupportive families, challenges in finding community, or fear of rejection. Identity-based stress, such as dealing with coming out, navigating one’s identity in various contexts, and the fear of experiencing violence or discrimination, further strains mental health. These conditions necessitate culturally-competent, affirming interventions to improve overall health for LGBTQ+ individuals.

In the context of gender and sexual diversity, changemakers must also consider the deep historical roots of discrimination and exclusion faced by queer, trans, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (QTBIPOC), which have shaped disproportionate impacts that persist today. Historically, many cultures recognized and celebrated diverse gender expressions, such as Two-Spirit, Māhū, and other third gender roles, before colonial and other repressive influences imposed binary gender norms. Today, Black transfeminine individuals face compounded levels of violence and systemic inequities, stemming from the intersections of racism, transphobia, and misogyny. Similarly, Two-Spirit and third gender individuals often grapple with the dual challenges of cultural identity erasure and accessing culturally-competent support.

Gender-expansive youth and individuals in rural areas are challenged by limited access to resources, healthcare, and community support. These issues are amplified in regions with hostile legislative climates where proposed laws restrict the rights and freedoms of transgender and gender-expansive people and foster environments of fear and isolation. Additionally, the concept of “gender refugees”—individuals who relocate to escape oppressive environments and seek safer havens—highlights the extreme measures some must take to attain acceptance and fundamental human rights. Addressing these issues requires a concerted effort to understand and dismantle the layered legacies of oppression that continue to impact gender-expansive communities today.

Joy can improve health outcomes for everyone, but for gender-expansive people, accessing joy has another layer of complication. Healthcare for gender-expansive people often solely focuses on “fixing” Trans peoples’ supposed brokenness and alleviating the debilitating condition of gender dysphoria. While this is critically important, “fixing” a negative experience should not be the end goal for the well-being of an entire community. The absence of gender dysphoria should not be the primary driver of Trans healthcare.Trans Joy as Healthcare

This is further complicated by the current legal landscape of Trans healthcare. Even in states that are supportive of gender-affirming care, many life-saving procedures—such as gender-affirming surgeries—require psychosocial assessments conducted by licensed mental health therapists to verify, in writing, that the gender-expansive person is experiencing enough dysphoria and distress for their procedure to be deemed a “medically necessary” and covered by insurance. However, if they are in too deep of distress—for example, having no social supports, contemplating suicide, and/or using substances—providers may refuse to conduct procedures until the person is “more stable.”

The practices of narrowly defining transness and universally pathologizing the Trans experience have created a system where Trans people have to repeatedly perform exactly the right amount of distress, despair, and self-hatred in order to access life-saving health interventions. Meanwhile, all of this maneuvering remains solely fixated on simply not feeling terrible.

Gender-expansive people deserve care and services that prioritize joy and, more specifically, Trans joy—an identity-based joy rooted in the liberation of gender-expansive individuals and communities. This means practicing gender-affirming, consent-based care, focused on cultivating positive health outcomes like joy and happiness. It also involves a mindset shift away from “curing” gender dysphoria, and toward prioritizing gender euphoria—a feeling of joy in how your gender is expressed, perceived, and experienced both internally and externally.

Cultivating Trans joy for individuals also advances joy equity for communities. Communities, in turn, are able to better support gender-expansive individuals. Momentum in this positive cycle increases the capacity of gender-expansive folks to engage in interdependence, connection, advocacy, collective care, and self-empowerment.

Learning from Trans-Wa: Health Equity through Trans Joy

The Transgender Health and Wellness Center of Washington (Trans-Wa) is a trans-led nonprofit organization that advances health equity and justice for gender-expansive people across Washington State by eliminating barriers to self-determination, building gender-expansive community and capacity, and driving institutional and systemic change. Long-term, they seek a future of mutual liberation where the infinite spectrum of gender is universally celebrated, especially for gender-expansive and historically marginalized individuals.

As one of Trans-Wa’s core values, Trans joy is infused throughout its strategies, programs, policies, and procedures. One of their signature events—Trans Day of Celebration—is entirely dedicated to building gender-expansive community, visibility, and joy. Trans-Wa has programs focused on Trans community and visibility, such as the Gender-Expansive Lending Library and forthcoming Gender-Expansive Book Club. Trans-Wa also cultivates joy through unique initiatives like their “pronouns companion” campaign, which features an illustrated gender-fluid cat character named Mewphoria, who changes colors and pronouns weekly. “Mewphie,” as the team affectionately calls them, helps people practice using gender-neutral, neo, and no pronouns in a way that is low stakes, low-barrier, and abundantly joyful.

Trans-Wa operationalizes joy throughout its strategies, policies, and procedures. Trans joy is integrated into their theory of change and strategic plan. It’s explicitly named in their contracts, handbooks, and policies. It’s infused throughout their branding and the colorful art (commissioned by a Trans artist!) featured across their platforms. It has a place in the weekly staff meeting agendas, and it has a home in the “celebration” and “positive Trans news” channels on Trans-Wa’s Discord server. This helps not only cultivate joy for their communities and program participants, but also for program staff, volunteers, and board members, many of whom are gender-expansive. It also gives them invaluable insight into what taking action for Trans joy looks like in practice.

Taking Action for Trans Joy and Joy Equity

Taking action to advance health equity through joy equity—and support gender-expansive communities in cultivating Trans joy—requires concerted efforts across all levels of social change.

At an organizational, institutional, and systemic level, we can:

Advocate for gender-affirming healthcare and practices that prioritize positive health outcomes over solely negating gender dysphoria

Center gender-expansive people in solution-building, decision-making, and positions of power related to care and services for gender-expansive communities

Have conversations around joy—especially Trans joy, Queer joy, Black joy, and other types of identity-based joy—and how this shows up in your work

Explore opportunities within your organization(s) to operationalize joy and joy equity

Engage in cross-movement solidarity and coalition-building between organizations focused on gender justice, LGBTQ+ justice, BIPOC communities, Disability justice, and other intersectional movements

Individually, we can:

Help gender-expansive friends, family members, and colleagues find joy during transition and feel safe in a transphobic world

Engage in affirming practices that we know improve mental health outcomes for Trans and gender-expansive people, such as using proper names, pronouns, and gender neutral language

Listen to and validate gender-expansive people experiencing minority stress and/or identity-based traumatic stress

Support creators and leaders who are bringing more Trans joy into the world, such as the contributors to this Trans Youth Joy zine

- Support organizations—like Trans-Wa and the Black Trans Fund—who purposefully and intentionally center and cultivate joy

--

AB Winter (they/them) is the Access, Visibility, and Engagement Manager at Trans-Wa. They are passionate about supporting the Trans and Gender-Expansive community through education and advocacy.

Serin Bond-Yancey (they/any) is a Disabled, queer, nonbinary, multiply-neurodivergent, antiracist accomplice. Serin serves as the Executive Director of the Transgender Health and Wellness Center of Washington (Trans-Wa), and works with a diverse portfolio of nonprofits as an Impact, Equity, and Accessibility Consultant.

More on Community Commons

Multiple Minority Stress and LGBT Community Resilience Among Sexual Minority Men

Resource - Journal Article

Beyond Inclusion: Pronoun Use for Health and Well-Being

Story

-

Original

Original

Brought to you by Community Commons

Taking Action for Trans Rights: Our Favorite Tools, Resources, and Data

Story

-

Original

Original

Brought to you by Community Commons

Related Topics